The Cost of Capital is the minimum rate of return, or hurdle rate, required on a particular investment for the incremental risk undertaken to be rational from a risk-reward standpoint.

Fundamentally, the cost of capital reflects the opportunity cost to investors, such as debt lenders and equity shareholders, at which the implied return is deemed sufficient given the risk attributable to an investment.

How is Cost of Capital Used in Finance?

In corporate finance, the cost of capital is a central piece in analyzing a potential investment opportunity and performing a cash flow-based valuation.

In short, a rational investor should not invest in a given asset if there is a comparable asset with a more attractive risk-reward profile.

Conceptually, the cost of capital estimates the expected rate of return given the risk profile of an investment.

The cost of capital is contingent on the opportunity cost, where alternative, comparable assets are critical factors that contribute toward the specific hurdle rate set by an investor.

The decision to allocate capital toward a given investment and to risk incurring a monetary loss is economically feasible only if the potential return is deemed to be a reasonable trade-off.

Hence, the cost of capital is also referred to as the “discount rate” or “minimum required rate of return”.

Why Does the Cost of Capital Matter?

Suppose an investor commits to a particular investment, at a time when there are other less risky opportunities in the market with comparable upside potential in terms of returns.

Ultimately, the decision to proceed with the investment would be perceived as irrational from a pure risk perspective.

Why? The investor deliberately chose a higher-risk investment without the gain of further compensation for incremental risk, which is contradictory to the core premise of the risk-return trade-off.

The risk-return trade-off in investing is a theory that states an investment with higher risk should rightfully reward the investor with a higher potential return.

Therefore, the capital allocation and investment decisions of an investor should be oriented around selecting the option that presents the most attractive risk-return profile.

The cost of capital is analyzed to determine the investment opportunities that present the highest potential return for a given level of risk, or the lowest risk for a set rate of return.

Of course, quantifying the risk of an investment (and potential return) is a subjective measure specific to an investor. However, as a general statement, the more risk tied to a specific investment, the higher the expected return should be – all else being equal.

Cost of Capital Formula

The cost of capital is the rate of return expected to be earned per each type of capital provider.

In particular, two groups of capital providers contribute funds to a company:

- Equity Capital Providers → Common Shareholders and Preferred Stockholders

- Debt Capital Providers → Banks (Senior Lenders), Institutional Investors, Specialty Lenders (Mezzanine Funds)

The incentive to provide funds to a company, whether the financing is in the form of debt or equity, is to earn a sufficient rate of return relative to the risk of providing the capital.

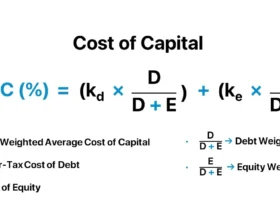

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the rate of return that reflects a company’s risk-return profile, where each source of capital is proportionately weighted.

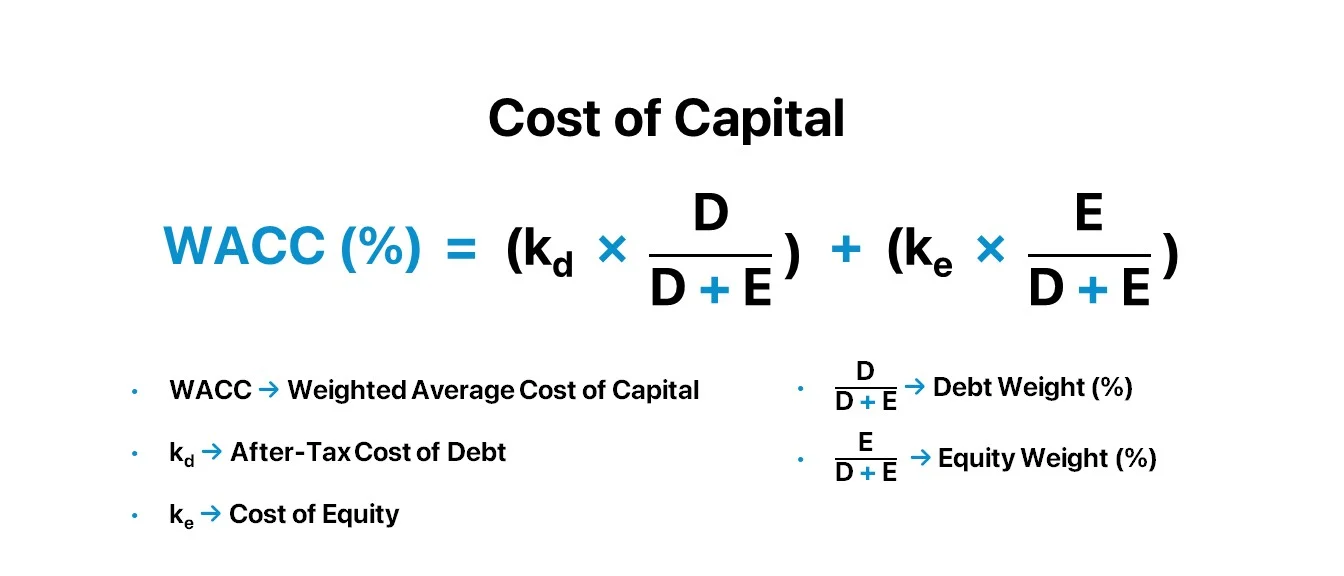

The formula to calculate the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is as follows.

Where:

- WACC → Weighted Average Cost of Capital

- kd → After-Tax Cost of Debt

- ke → Cost of Equity

- D / (D + E) → Debt Weight (%)

- E / (D + E) → Equity Weight (%)

How to Calculate Cost of Capital

The step-by-step process to calculate the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is as follows.

- Step 1 → Calculate After-Tax Cost of Debt (kd)

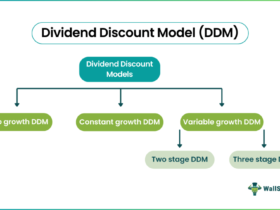

- Step 2 → Calculate Cost of Equity (ke) with the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

- Step 3 → Determine the Capital Weights (%)

- Step 4 → Multiply Each Capital Cost by the Corresponding Capital Weight

- Step 5 → Sum of the Capital Structure Weight-Adjusted Capital Costs is the Cost of Capital (WACC)

One crucial rule to abide by is that the cost of capital and the represented stakeholder group must match.

The cost of capital metric and corresponding group of represented stakeholder(s) are each outlined here:

- Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) → All Stakeholders, Including Debt, Common Equity, and Preferred Stock

- Cost of Equity (ke) → Common Equity Shareholders

- Cost of Debt (kd) → Debt Lenders

- Cost of Preferred Stock (kp) → Preferred Stockholders

Step 1. Calculate Cost of Debt (kd)

The starting point to compute a company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the cost of debt (kd) component.

The cost of debt (kd) is the minimum yield that debt holders require to bear the burden of structuring and offering debt capital to a specific borrower.

Conceptually, the cost of debt can be thought of as the effective interest rate that a company must pay on its long-term financial obligations, assuming the debt issuance occurs at present.

Or said differently, the cost of debt is the minimum required yield that lenders expect to receive on a financing arrangement, where there is adequate compensation for the potential risk of incurring a capital loss from providing debt to a specific borrower.

Estimating the cost of debt is relatively straightforward in comparison to the cost of equity since existing debt obligations such as loans and bonds have interest rates that are readily observable in the market via Bloomberg and other 3rd party data platforms.

Referencing the market-based yield from Bloomberg (or related resources) is the preferred option, and the pre-tax cost of debt can also be manually determined by dividing a company’s annual interest expense by its total debt balance.

The formula to calculate the pre-tax cost of debt, or “effective interest rate,” is as follows.

Since the interest paid on debt is tax-deductible, the pre-tax cost of debt must be converted into an after-tax rate using the following formula.

Contrary to the cost of equity, the cost of debt must be tax-affected by multiplying by (1 – Tax Rate) because interest expense is tax-deductible, i.e. the interest “tax shield” reduces a company’s pre-tax income (EBT) on its income statement.

The yield to maturity (YTM) on a company’s long-term debt obligations, namely corporate bonds, is a reliable estimate for the pre-tax cost of debt for issuers who are ascribed investment-grade credit ratings, which are determined by independent credit agencies (S&P Global, Fitch, and Moody’s).

Investment-grade debt is deemed to carry less credit risk and the borrower is at a lower risk of default; hence the designation of a higher credit rating.

Usually, the book value of debt is a reasonable proxy for the market value of debt, assuming the issuer’s debt is trading near par, instead of at a premium or discount to par.

The higher the cost of debt, the greater the credit risk and risk of default (and vice versa for a lower cost of debt).

The section on cost of debt was helpful. Knowing how to calculate after-tax costs can help companies make better financial choices.

This post made it clear that higher risk investments should offer higher returns. It’s about finding a good balance.

I learned that the cost of capital is like a minimum return rate. Investors should compare it to other options before investing.

I find it interesting how the article explains calculating cost of capital with different steps. It seems useful for making investment decisions.

The article explains that the cost of capital is important for investors. It helps them decide if an investment is worth the risk.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

shnqi0

jgcxq0

sxglv4

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

6ik3r1

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://www.binance.com/join?ref=P9L9FQKY

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

What i do not understood is if truth be told how you are no longer actually a lot more smartly-preferred than you may be now. You’re so intelligent. You understand therefore significantly in relation to this matter, made me personally imagine it from so many varied angles. Its like women and men aren’t involved unless it is something to accomplish with Girl gaga! Your personal stuffs outstanding. Always maintain it up!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Oh my goodness! a tremendous article dude. Thanks However I am experiencing issue with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody getting identical rss problem? Anyone who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx

t5xguv

Usually I don’t read article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do so! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thanks, quite nice article.

Hi there! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 4! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the outstanding work!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.